May 19, 2017

June 13, 2017

UPDATE: The State of Illinois has renegotiated the termination thresholds on four of its five interest rate swaps to help avoid termination fees if the State’s credit rating is downgraded further.

Original post published on May 19, 2017

With the end of the Illinois General Assembly legislative session looming and a budget compromise still out of reach, the potential for ratings downgrades once again threatens to trigger termination of Illinois’ interest rate swap agreements, which would cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars.

Governments enter into interest rate swaps on variable-rate bonds in order to save on total interest payments compared with what they would pay by issuing standard fixed-interest bonds. In doing so, they take on a number of risks associated with both the swaps and the underlying variable rate bonds. A deeper examination of how these agreements work shows how some of these risks have become more likely for Illinois as the State’s fiscal condition worsens.

How Swaps Work

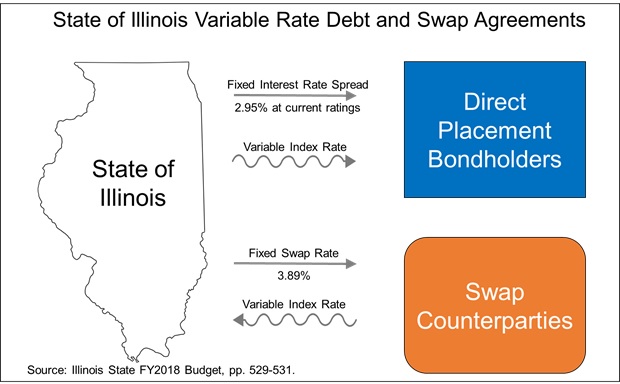

Interest rate swaps can come in many varieties, but all of Illinois’ are “synthetic fixed rate.” That means that the swaps are designed to “fix” the variable interest rate of the associated bonds. The State pays a variable interest rate plus a fixed spread to the bondholders. The State receives a variable rate from the swap counterparties that roughly cancels the rate the State pays to the bondholders. In exchange, the State pays the swap counterparties a fixed interest rate.

The following diagram illustrates the type and direction of payments for the State’s variable rate debt and swap agreements.

The net result of these payments is a (mostly) fixed rate that endures for the life of the bonds and the swaps, regardless of prevailing interest rates. The only time the interest rate varies is when the two variable rates differ from each other. However the amount of this variation is usually small. The variable rates of both the bonds and the swaps are based on one of two floating-rate indices: 1-month LIBOR or SIFMA. With the rates for May 17, 2017, the weighted average floating rate paid by the State on all of the bonds and swaps is negative 0.076%, meaning that the State receives slightly more in floating interest from the swap counterparties than it pays in floating interest to the bondholders.

Critics of swaps often portray them as a bet that future interest rates will be high, in which case issuers such as Illinois will receive more from the counterparty than the fixed rate that they pay. Conversely, if rates are low, then the issuer “loses” and the counterparty “wins.” But this inaccurately portrays swaps as the only instance in which an issuer takes a risk involving interest rates. When an issuer sells un-swapped variable rate bonds, it is inherently betting that interest rates will be low. When it sells regular fixed rate bonds, it is betting that interest rates will climb higher. A synthetic fixed rate swap, like Illinois’, puts the issuer in roughly the same risk position with regard to interest rates that it would be in with regular fixed rate bonds.

There are still two serious risks involved, however, but they have more to do with the State’s ability to maintain its credit rating, which has proven problematic in recent years. The first is rollover risk, which is associated with variable rate bonds regardless of swaps. The second is termination risk, which is associated with the swaps.

Variable Rate Debt and Rollover Risk

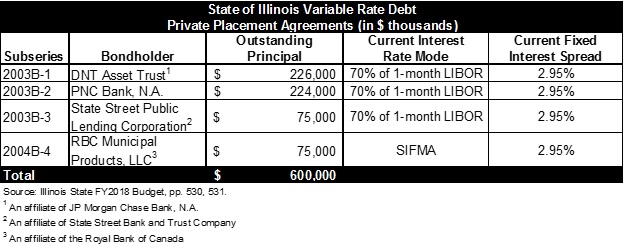

Illinois has a single series of variable rate bonds, Series 2003B, with an outstanding par of $600 million. As of May 17, 2017, the variable rate that would be paid by the State on the bonds is between 0.70% and 0.78%. Like many variable rate bonds, this series originally guaranteed the holders the right to demand repayment at any time (known as a “put” option). In order to prevent a sudden financial burden, Illinois entered into agreements with banks that would remarket the bonds if they were put, and to buy the bonds if no other purchaser could be found. These agreements, known as letter of credit facilities, expire periodically and need to be renegotiated. However, if the issuer’s credit rating is low, banks demand more compensation if they are concerned that the bonds might be difficult to remarket.

The States’ previous letter of credit facilities expired last year. However, due to the State’s low ratings, it would have been more expensive[1] to renew those facilities than to pay banks to purchase the bonds directly (known as a direct placement). Under the direct placement agreements negotiated in November, the State pays four bondholder banks interest on the bonds that are based on one of the two floating indices. In addition, the State also pays a fixed interest spread of 2.95%. Together, the fixed interest spread, the fixed rate paid on the swaps and the variable rate payments produce a current weighted average interest rate on the bonds is 6.76%.

The fixed spread could increase if the State were downgraded, but the publicly available documents[2] do not disclose by how much. Additionally, the agreements will expire in November 2018, and if the State’s ratings do not improve by that time it could face additional costs as well as the risk that it cannot find anyone willing to “rollover” the bonds.

The following table shows the current status of the underlying variable-rate bonds.

Interest Rate Swaps and Termination Risk

Illinois’ interest rate swaps cover the entire $600 million of variable rate debt, and consist of agreements with five counterparties. The State pays each party a fixed rate of 3.89% and receives a variable rate based on 1-month LIBOR or SIFMA. As of May 17, 2017, the variable rate that would be paid to the State on the swaps is between 0.78% and 0.84%.

Based on these rates, each swap has a value at any given time that represents the total value of all remaining payments under the swap by both parties. When 1-month LIBOR and SIFMA are higher, the value to the State goes up. When they are low, as they have been for several years, the present value to the State can be negative.

As of December 31, 2015 the State’s swaps portfolio had a negative value of $138.0 million. While the value worsened to negative $153.3 million during the low interest rate environment of 2016, rising interest rates since that period improved the present value to negative $114.2 million as of December 31, 2016, and negative $107.9 million[3] as of March 31, 2017.

The following table summarizes the terms of each swap agreement as well as the changes in present value over the course of calendar year 2016.

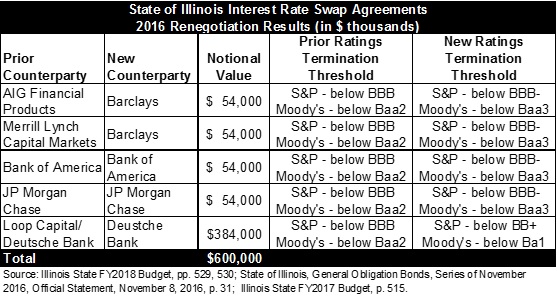

Under the terms of each contract, if the State’s credit rating falls below a certain threshold the deal is terminated and the State must pay the market value of the deals at the time of the termination. The State then would continue to pay the variable rate interest on the underlying variable rate bonds.

Due to the State’s deteriorating credit quality, the State entered negotiations with all counterparties during 2016. Two of the swaps were transferred to a new counterparty, and all of the swaps now have lower ratings termination thresholds. The following table shows the results of the negotiations.

Illinois currently carries ratings of BBB from S&P and Baa2 from Moody’s, both with negative outlooks. Without the renegotiations, any downgrade by either company would have terminated all five agreements. However, as a result of the renegotiations, it would take a three-notch downgrade by either company to terminate all five swaps. A much-more-likely two-notch downgrade by either Moody’s or S&P would trigger termination of all but the Deutsche Bank Swap, which is approximately 64% of the total present value. If such a double downgrade had occurred on March 31 (the last available valuation date) the State would have faced a termination payment of approximately $39 million.

The State has been warned that further downgrades could be forthcoming as soon as the end of May 2017 if the budget impasse is not resolved. In a report issued in March, Moody’s warned that “failure to reach a consensus before the current legislative session adjourns on May 31 would signal deepening political paralysis, heightening the risk of creditor-adverse actions.” On April 20, S&P downgraded the City Colleges of Chicago and six State universities, and issued a negative credit watch for a seventh. The ratings actions pointed to the State budget impasse. These reports signal a high risk of downgrade if a balanced budget is not in place at the end of the session. Whether either potential downgrade would be two notches and trigger the swap terminations remains to be seen.

If the downgrades are sufficient to trigger the swaps, the State may still have some flexibility in paying for the terminations. In March 2015 both the City of Chicago and Chicago Public Schools received ratings downgrades sufficient to trigger terminations of their swaps. In those cases the counterparties were willing to negotiate to grant forbearances and discounts.[4] The City ultimately paid $359.0 million[5] and CPS $234.3 million[6] to terminate their swaps over the course of FY2015 and FY2016.